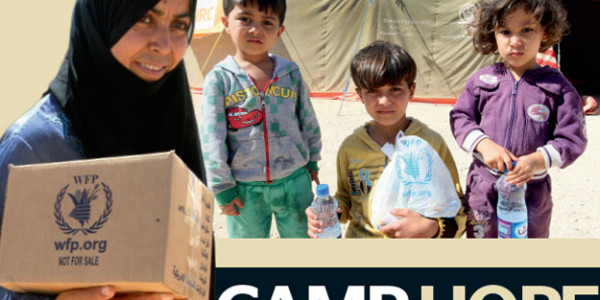

Syrian refugees learn to cope with harsh realities of life Nivriti Butalia & Leslie Pableo / 31 May 2013 People displaced by war in Syria learn to cope with harsh realities of life at a camp in Jordan Blonde-haired teenaged boys in trousers that fall short of their ankles pushing wheelbarrows piled high with food cartons. Women in printed hijabs and black abayas carrying bags — and, if a hand is free — shielding their eyes from the sun. Large spirals of barbed wire fencing, land rovers and SUVs with UN number plates, dust-coated sedans stocked with household supplies and that serve as mobile homes. A chain of water trucks forming a mini traffic jam, and clusters of men milling around, smoking cigarettes, and sizing up each new car that draws closer to the security check. This is what you see in the 50 metres before entering the gate of Zaatari, the refugee camp for Syrians in the Mafraq Governate of Jordan. A worker with UN agency World Food Programme (WFP) at the camp says, “We prefer to call them beneficiaries – refugees doesn’t sound right”. Once inside, it’s more of what you see outside. You also see a sign that reads ‘Avenue Champs Elysees Paris’, indicating the way to an unregulated bustling market place where you can source everything from dustpans and fruit juices to wedding dresses and mobile chargers — all at a cost, of course, and money is scarce. Walking down Zaatari’s Champs Elysees many different sounds and tongues resonate. Besides the high-pitched “hello!”, “Sala’m walekum!”, and even the odd “I love you!”, there are broadly two reactions. Some see the camera, get angry and mutter their protests. They fear their photographs will be aired on TV and their relatives in Syria will have a price to pay. So they turn away and cuss. Others do the opposite. They rush to position themselves in front of the lens, posing, shrieking, laughing, parting forefinger and middle finger, making the universal sign for a victory, and baring teeth surprisingly undamaged by the constant intake of nicotine. Everyone at Zaatari seem to love cigarettes. Take Fatima, for instance, who seated in her tent, on the jute mats provided by UNHCR, flicks ash from a borrowed cigarette. The brand? – Gitanes, from a pack that a UN worker offered. The ash is tipped in a flat shallow empty that may well have contained tuna – a component of dry rations that WFP provides. WFP is working to end the dry ration spell and replace it with a food voucher scheme that, besides being a lot more logistically-sound for WFP – they won’t have to fly in massive quantities of cardboard cased beans and wheat — this gives refugees the freedom and dignity to buy what they want, even yoghurt or ketchup – neither seen as essential food. No alcohol and cigarettes, though. Those are luxuries that will not be covered by emergency aid. Fatima, tipping her cigarette, says she hasn’t smoked since she was young and would sit with her girlfriends and gossip. Fatima is 39. She’s been at Zaatari since November. Before which she was at Yarmoukh — the Palestinian camp in Damascus. She’s here with her three younger brothers. A fourth joined rebel forces in Syria. BIRTH PANGS: Ruba, 26-years-old Syrian wth her baby at a hospital at the Zaatari Syrian Refugee Camp. Fatima is unmarried but she had ring that she sold to buy a TV so she can get news in her tent of her village. Her house was bombed and she doesn’t want to go back. Even though she’s sick of eating the same food, she says her life is much better here. She wishes she had money to buy detergent and yoghurt, and olives, and shoes so she didn’t have to borrow a pair from her friend and neighbour (whom she met at the camp) Umm Shadi, whenever she has to go collect her daily loaf of bread. The need for detergent is especially acute. Over time Fatima’s mattresses have gotten dirty and they’re not easily replaced. As an alternative, she’s wrapped her black mattresses in a plastic sheet so she can clean it with water, a resource more scarce than clean mattresses. The sight of crowds is consistent all throughout the crowds of people carrying water, bags, boxes, vegetables, and babies – An average of 70 babies are born in Zaatari every week at the Gynécologie Sans Frontières tent, the only ‘delivery room’ at the camp. Zaatari, set up on 29 July 2012, is the second largest refugee camp in the world — Dadaab in North East Kenya they say is the largest. FUN TIME: Syrian refugee children having fun after the WFP feeding programme. But unlike Dadaab, Zaatari hasn’t been around that long and it is already a township. Two thousand Syrians cross the border into Jordan every day. At present, UN officials say there are “definitely over 100,000 people in the camp”. The numbers multiply daily. It’s difficult to keep track as people come in hordes. There is a necessary registration that happens when they enter the camp — most arrive at night – but there is no de-registration for those who leave. The numbers tell their own story. Donations filter in, but there is a worry that donor fatigue will set in and make food and aid all the more precious. As far as philanthropy goes, the UAE donated a Toyota pick-up and a generator in December 2012 to WFP operations for Syrian refugees in Syria’s neighbouring countries. There is even a new camp managed by the Emirati Red Crescent called the Emirati Jordanian Camp that opened on April 10 near Amman, a 45 minute drive from Zaatari, set up in the middle of muted sand-skree-pink oleander bushes infested landscape. The camp has a capacity to house over 5,000 people and they plan to push that up to 25,000. BARBED CHATTER: Syrian men hang out on ‘Des Champs Elysees’. Laure Chadraoui, the WFP spokesperson in Jordan, says: “Thanks to the support of many donors including the UAE, we were able to provide food assistance to Syrian refugees.” She says: “We have a strong partnership with the UAE who since 1973 has contributed over $18 million to WFP’s food assistance worldwide.” Laure’s worry is that donations will dry up. “As people continue to flee the conflict in Syria, we will scale up our operations to reach 3.6 million refugees — four times the number of refugees we are reaching now. In order to continue our food assistance, and step up our operations, we seek to raise over one billion dollars to meet the food needs of people affected by the conflict.” BARBED CHATTER: Syrian men hang out on ‘Des Champs Elysees’. In the first three months of the camp, WFP served three million hot meals to the refugees, cooked in Amman. The meals were mostly rice and chicken, rice and meatballs with zucchini. This wasn’t cost effective. As well, that people were tired of eating the same thing day in and day out. So the WFP switched to dry food rations — cartons of which are often seen piled high on those wheelbarrows and pushed by young boys. The box is made up of pasta, bulgur wheat, rice, lentils, macaroni, vegetable oil (“Chef’s choice, 100 per cent sunflower oil”), sugar and salt. UNHCR provides free food that includes tomato paste, canned meat, tuna, tea, beans, halawa and hummus. To call it a camp is inaccurate. Even ‘township’ is off the mark. In its own right — with over 28,000 shelters and an approximate 12,000 caravans and 16,000 tents and over a 100,000 people within the 530.95 hectares boundaries of the ‘camp’ – Zaatari is a fast-growing metropolis. — nivriti@khaleejtimes.com Taylor Scott International

Syrian refugees learn to cope with harsh realities of life

This entry was posted in Dubai, Education, Entertainment, Investment, investments, Kenya, News, Sports, Taylor Scott International, TSI, Uk and tagged business, dubai, entertainment, facebook, food, georgia, kenya, news, sports, tsi, windows. Bookmark the permalink.